Marine Snails

Snail Menu

Snails

Snail Anatomy

Mud Dog Whelk (Mud Snail)

Moon Snails

Radula

Slipper Shell

Oyster Drill

Murex Snails

Class Gastropoda Latin: gaster=stomach podus=foot

Marine Snails

Worldwide, there are over 40,000 recognized species of snails consisting mostly of marine snails of which, several species inhabit Barnegat Bay

Fun Fact: When the word “snail” is used in a general sense, it includes land snails, numerous species of sea (marine) snails and freshwater snails.

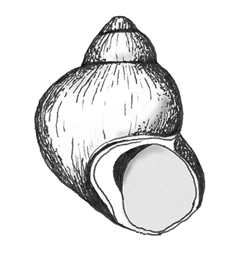

Snails are univalves, meaning they have one shell (valve) to which they can retract their whole body into when threatened.

Snails are univalves, meaning they have one shell (valve) to which they can retract their whole body into when threatened.

They can be algae eaters (algivorous), feed on other animals (carnivorous) or feed on both plants and animals (omnivorous) as predators and scavengers.

To find out more about snails and whelks that develop a shell with a single opening to do what bivalves do by opening their two shells.

To find out more about snails and whelks that develop a shell with a single opening to do what bivalves do by opening their two shells.

Click here to read about <torsion>

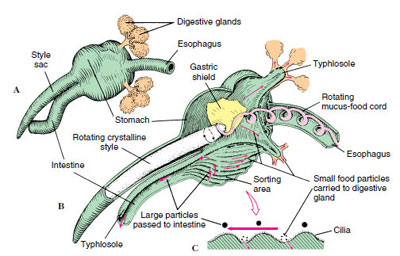

The snail crawls and climbs with its foot. A spiral shell protects its internal organs, including the stomach, the digestive tract, the heart and blood vessels, the kidneys, and the gonads.

A thin membrane, called the mantle, protects these organs and also secretes the shell.

When a snail withdraws into its shell, a small disk attached to foot called an operculum seals off the entrance.

While the shell is the snails primary means of protection, the ability to adhere to a surface and in some species, production of noxious compounds also offer protection from predators.

Projecting out in front of the snail are two tentacle which are used for sight.

Another set are used for touch. Below these tentacle is the mouth.

Most snails have thousands of microscopic tooth-like structures located on a tongue-like ribbon called a radula. The radula works like a file, ripping the food into small pieces

Mud Dog Whelk Tritia obsoleta (formerly Ilyanassa obsoleta)

The mud dog whelk (also called eastern mud nassa, eastern mud snail, mud basket shell, common mud snail) is about ¾ of an inch in length.

The mud dog whelk (also called eastern mud nassa, eastern mud snail, mud basket shell, common mud snail) is about ¾ of an inch in length.

It has a chalky white shell, but is covered by a dark brown to red-brown periostracum. It has 6 whirls and an operculum.

Theses snails form large clusters that tend to be divided into age groups. They are always found in large numbers, sometimes in the hundreds of thousands.

Mud snail is a detritus feeder (omnivore), eating whatever is found in the film on top of the mud where it lives including many microscopic marine plants.

As scavengers, they are attracted to bait or dead fish.

Theses snails form large clusters that tend to be divided into age groups.

They are almost always found in large numbers, sometimes in the hundreds of thousands.

The snails leave a mucous trail as they glide along the bottom. The mucous is a chemical trail marker. Other snails will find the trail and follow it.

The only time this does not seem to hold true is if one of the snails is sick or injured. The other snails will quickly abandon the unfortunate snail.

New England Dog Whelk Nassarius trivittatus

New England dog whelks are small snails distinguishable by their pointed spiral shells, which have raised beads along the ridges and sharp, scalloped outer lips.

New England dog whelks are small snails distinguishable by their pointed spiral shells, which have raised beads along the ridges and sharp, scalloped outer lips.

The shell ranges in color from white to yellowish grey to dark reddish brown.

They feed mostly on dead fish but are capable of drilling holes in the shells of bivalves using an organ called the radula. The radula is a tooth-covered drill used to bore a small hole into the hard shell of other mollusk.

After drilling the hole, the dog whelk can feed upon the soft flesh of its prey.

When feeding on barnacles, however, they will pry open the top plates rather than drill a hole.

Common Periwinkle Littorina littorea

The common periwinkle snail, scientific name: Littorina littorea, is not a native species of the North American and Canadian shores.

The common periwinkle snail, scientific name: Littorina littorea, is not a native species of the North American and Canadian shores.

It was introduced to these waters in the mid 19th century from Western Europe and rapidly spread along the Northeast coast.

There are many theories regarding their presence along the North American shores.

It is believed that they may have been transported across the Atlantic in the ballast waters of ships,

They may have been intentionally released or brought by colonists who wanted a familiar source of coastal food.

The introduction of the common periwinkle has impacted the ecosystem on the North American and Canadian shores.

The introduction of the common periwinkle has impacted the ecosystem on the North American and Canadian shores.

It has drastically changed the distribution and abundance of algae on rocky surfaces and altered the relationship of organisms in their habitat.

It has also been responsible for the displacement of some native species.

Their voracious feeding is also responsible for the disappearance of larger seaweeds.

The periwinkle shell is broadly ovate and contains six to seven whorls with some fine threads and wrinkles.

The periwinkle shell is broadly ovate and contains six to seven whorls with some fine threads and wrinkles.

The color varies from grayish to gray-brown, often with dark spiral bands.

The base of the columella is white and lacks an umbilicus.

The white outer lip is sometimes checkered with brown patches.

The inside of the shell is chocolate brown.

L. littorea is oviparous, reproducing annually with internal fertilization of egg capsules that are then shed directly into the sea. Planktotrophic larvae develop in four to seven weeks.

Females lay 10,000 to 100,000 eggs contained in a corneous capsule from which pelagic larvae escape and eventually settle to the bottom.[8] This species can breed year round depending on the local climate.[8] Benson suggests that it reaches maturity at 10 mm and normally lives five to ten years.[8] while Moore suggests that maturity is reached in 18 months.[18] Some specimens have lived 20 years.

Female specimens have been observed to be ripe from February until end of May, when most are spawning. Male specimens are mainly ripe from January until the end of May and lose weight after copulation. The young seem to settle primarily from the end of May to the end of June.